At the age of about 10, Joshua was despatched to a boarding school for young gentlemen. His father's business was seemingly still prospering and it was time for the self-willed and impetuous boy to be tamed and educated in preparation for a bright future. Many fathers in this period were content to banish their children for years on end to schools that proclaimed the advantages of not allowing any holidays but in Joshua's case there was clearly no lack of fatherly affection. However, it was equally obvious that, with his father having taken a common law wife and then started a second family, there was no place at home for Joshua and his sister Sarah. So Joshua went off to Mr Baron's Knowsley Academy, just outside Liverpool.

Sir Joshua evidently recalled schooldays in Knowsley with considerable fondness. His son Hugh described them in his biography as the three brightest years of Joshua's boyhood. Joshua spoke of Mr Baron with affection and respect and had formed many life-long friendships, not least with his future wife's brother. Knowsley Academy was on the borders of Knowsley Park, which contained the seat of the Earl of Derby. For amusement the boys used to make apple-pies, baking the pastry in holes in the ground and one day they were observed by the Earl. Thereafter he often visited them and ensured his popularity by giving the boys money. The Knowsley idyll ended when John Walmsley's business failed and he could no longer afford the school fees.

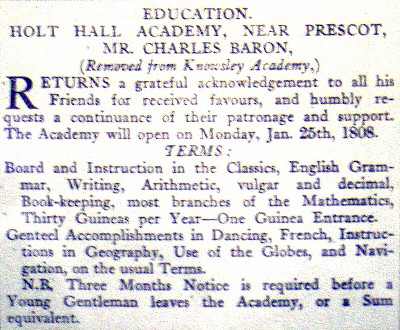

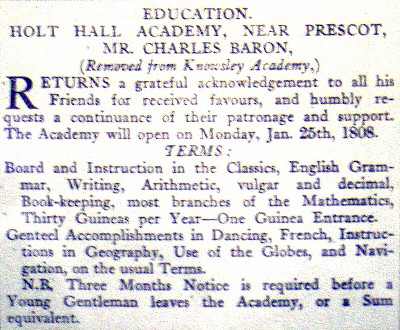

Charles Baron plied his schoolmaster's profession in and around Knowsley for over 40 years, probably commencing in the late 1780s and continuing till his death in 1830. We know from a newspaper advert in early 1808 that he ran Knowsley Academy up to the end of 1807 and then removed himself just a few miles to Holt Hall near Prescot. Holt Hall Academy continued up until at least 1818, after which Baron moved again to Whitfield House in nearby Roby, styling his school Roby Academy. After his death this school was run by his sons John and Thomas, who had no doubt assisted their father during his lifetime.

A description of life at Holt Hall Academy was provided by the soldier and novelist Meadows Taylor, who spent an unhappy year or two there in about 1816-7. Like similar accounts of school life, it was composed some years after Charles Dickens had savaged private schools in the north of England in Nicholas Nickleby and thereby created an expectation on the part of readers. Taylor was just 9 when he left Holt Hall but he tried to be fair in his subsequent memoirs (The Story of My Life, 1878):

There were, I believe, about a hundred boys, and the school had a wide reputation. It was a rough place, although scarcely equal to the Yorkshire school of Mr Squeers; but I, fresh from the gentle presence and teachings of my mother, felt the change keenly, and was almost inconsolable - so much so, that I was sent home after a while, and when I returned to Mr Barron's, it was as a parlour boarder, a distinction which caused much jealousy, and subjected me to much torment. I was the youngest boy in the school, teased and bullied by all; but after I had received an enormous cake from home, which was divided among the boys, I grew more into favour, and even became a "pet" among them.

We rose at six in summer, partially dressed ourselves, and, with our jackets over our arms, went down to a stone bench in the yard, where stood a long row of pewter basins filled with water, and often in winter with ice. Here, in all weathers, we washed our faces and hands, combed and brushed our hair, and went into the schoolroom a while to study; then were let out to play till the bed rang for breakfast, consisting of fresh new milk, and a good lump of bread. At ten we were all in school again, and work went on, only interrupted by the instances of severe punishment which but too often occurred. The rod was not sparingly used, as many a bleeding back could testify, and I have often been obliged to pick the splinters of the rods from my hands.

We were well fed on meat, cabbage, and potatoes, and rice or some plain pudding; on Sundays we had invariably roast beef and Yorkshire pudding. We went into school again at three. At five school broke up, and at seven we had our suppers of bread and milk; afterwards we could study or go out within bounds as we pleased. Good Mrs Barron attended to our personal cleanliness and to our health; and at stated seasons, especailly in spring, we were all gathered together in the dining-hall, where the old lady stood at the end of the room at a small table, on which was a large bowl of that most horrible compound, brimstone and treacle. The scene rises vividly before me, as we all stood with our hands behind our backs, opened our mouths and received each our spoonful, swallowed it down as best we could - and had to lick the spoon clean too! Surely this was a refinement of cruelty!

What Meadows Taylor wrote about Holt Hall Academy was probably indicative of life at Knowsley Academy a few years earlier and is not inconsistent with Joshua Walmsley's recollections of schooling by Mr Baron. Baron evidently had a good reputation as a schoolmaster, despite his fondness of the rod, and was able to attract the sons of both the Liverpool nouveaux riches like John Walmsley and the spirits merchant Hugh Mulleneux and those from more established families like the merchant Philip Meadows Taylor. For many years Baron owned or leased a property in Berry Street just doors away from John Walmsley and this may well have brought the two into contact before the young Joshua was sent off to school. Baron's fees for boarders at Holt Hall Academy of 30 guineas per annum were really quite expensive, though more costly schools could be found further south. Once John Walmsley's business started failing, it is no surprise that he looked around for a cheaper alternative. A parliamentary portrait of Sir Joshua Walmsley in the Illustrated London News in 1849 mentions that he was educated at Holt Hill [sic]. This may mean that he stayed with Baron after his removal from Knowsley to Holt Hall and was still there in 1808.

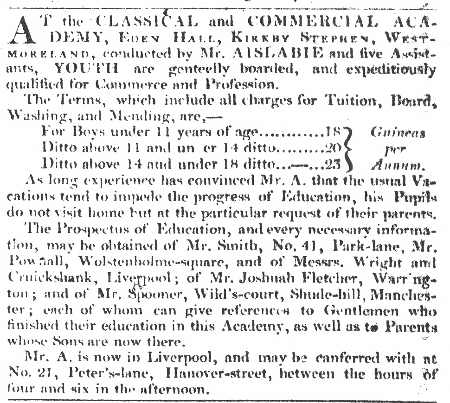

At the age of about 12 or 13, Joshua was uprooted from Mr Baron's school and sent to be educated in Kirkby Stephen in Westmorland at Mr Aislabie's school, later known as Eden Hall Academy. Eden Hall was one of a clutch of schools in Westmorland and Yorkshire that offered economical education for the sons of gentlemen. In early 1808 the cost of boarding for a child of Joshua's age was 18 guineas per annum, as compared with the 30 guineas charged by Charles Baron. Following the furore created by Charles Dickens' depiction of Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby, which was published in 1838-9, these schools eventually disappeared but even before then they were quite often short-lived. Eden Hall did not survive beyond the death of its founder in 1818. By contrast, Baron's last school, Roby Academy, survived his death by many years.

Life at Eden Hall was spartan but, in his subsequent reminiscences (quoted by his son Hugh in his biography), Sir Joshua wrote of it with a surprising degree of affection, given his experiences there:

Breakfast at Eden Hall consisted of a slice of black rye bread, a large proportion of bran entering into the composition. As a rule it was sour. In addition, a large boiler was placed on the table half filled with water, and into this two gallons of milk had been poured, and some handfuls of oatmeal added. Its contents were shared by the one hundred and thirty hungry lads. Sometimes oatmeal porridge replaced the contents of the boiler, and a teaspoonful of treacle was allowed as a great treat. Three times a week we had a limited amount of meat for dinner; on other days, potatoes, black bread, and cheese. This cheese had grown so hard with age we nicknamed it "wheelbarrow trundles"; the third meal consisted of another slice of bread and of the "trundle" cheese.

For a certain number of hours daily we were turned into agricultural labourers, working on a large belonging to our master. We were a healthy set, our constitutions hardened by outdoor life and labour. Some boys complained, some ran away, but none went ill, and only one death occurred during the six years I stayed there.

Some of the school's activities had a distinctly Westmorland flavour:

The pupils of the school contested matches in football, cricketing, and other games, with the townspeople, and in the majority of cases came off victorious. At all times Westmoreland has been noted for its wrestling, and to excel in this, as in other sports, was a point of honour with the school. When one of their number was declared by his master to be their best man in muscle and address, he would march into the town and throw down his gauntlet in the presence of the inhabitants. This consisted in pulling the bell in the public market-place, and waiting there till a rival champion appeared. The sound of the bell was perfectly understood by the townsfolk. It was a challenge to any antagonist who would offer himself for the best of three falls. The match was conducted in the most friendly manner, with perfect good humour, and the beaten lad went home to town or school to practise again, and when ready to toll the market-bell once more.

Once past the small town of Kirkby Stephen, the country extended for miles in heather-covered moors. Thickly tenanted with grouse, they stretched wild and desolate for a great distance towards Bowes. Mr Aislabie [the headmaster] shot over these moors, and one day took me with him to carry his spare gun. ~ It happened that ... a grouse rose at my feet. The temptation was great; in an instant my finger was on the trigger. I fired, and to my delight and surprise the grouse fell. ~ Keen eyesight and unerring precision served my turn, and with my single gun I brought down three brace of grouse. ~ [Aislabie recognised this potential and sent young Joshua off on regular expeditions to hunt grouse, which fetched a good price in the local market.] My gun, ammunition, a bag wherein to bestow the game, a luncheon consisting of black bread and a piece of wheelbarrow trundle cheese, composed my equipment, and very soon the funds of Eden Hall so profited by my gun, that instead of the day being spent on the moor and the night in my bed in the dormitory, it came to pass that I was sent off on excursions of a fortnight's duration. A donkey-cart was allotted me to carry the ammunition and a considerable amount of black bread and venerable cheese. A companion, by name Francis, was also given me. ~ His duty was to carry the gun and fishing-gear. We dragged the tarns by night and, and when a goodly cargo of grouse had been shot, Francis would harness the donkey to the cart, and taking charge of game and fish, would deliver all to the headmaster. We got no share of the booty ...

In due course Joshua became an assistant master at the school. He was entrusted with the school accounts and also assigned the task of making out the bills for the boys' parents:

Between each [hunting] campaign I returned to the school-room, studied, taught, and had charge of the bills.

With his father now dead and his future prospects uncertain, Joshua would have stayed longer at Eden Hall, had he not had a quarrel with Aislabie's brother and decided to depart:

One morning, in the spring of 1811, carrying all my worldly goods - they were not a heavy load - I bade farewell to Eden Hall. I travelled by carrier as far as Kendal, then took an outside seat on the conveyance that at Warrington met the Liverpool coach. After I had paid my fare but a few shillings remained in my pocket.

Eden Hall no longer survives. In 1818 the premises became the Kirkby Stephen workhouse and they were finally demolished in the 1970s. A detailed account of the quest to locate Eden Hall and identify its headmaster may be found here. For 10 years or more the school occupied a prominent place in the life of Kirkby Stephen and it's strange that so little evidence of its existence remains.

The proprietor and headmaster, Richard Aislabie, was born in Bowes in 1774. He may, as Sir Joshua states, have had a farm but there is no evidence that he owned any of the premises used for his school in Kirkby Stephen. Nothing is known of Aislabie's academic background (he makes no mention of qualifications in his adverts) but before he moved to Kirkby Stephen he was probably teaching in Derbyshire. For a period he was joined at Eden Hall by his younger brother Thomas, who subsequently became a grocer. Another brother, William, also became a schoolmaster.

Aislabie probably began teaching in Kirkby Stephen in late 1807, initially in partnership with Thomas Robinson at Vicarage House, a mansion overlooking the River Eden built in about 1760 by the then vicar Henry Chaytor. At the end of 1808 Aislabie and Robinson dissolved their partnership and Aislabie carried on as sole proprietor of Vicarage House. In 1809 his uncle, Richard Binks, a merchant from Kingston-upon-Hull, purchased a set of buildings near the church known as the Manufactory and it was almost certainly here that Aislabie established Eden Hall Academy. No photographs seem to exist, the only known depictions being some drawings by Anne Anderson in her (and Alec Swailes') book Kirkby Stephen (1985). From Anderson's drawings, what became the main workhouse building was a large three-storey stone edifice with a small classical portico. Most of the facade was in the form of a large country house but the end next to the churchyard had much smaller windows. From maps it seems that two large wings extended behind the building. It is this main workhouse building that constitutes the best candidate for the grandly named Eden Hall.

Walmsley recalled that he had attended Eden Hall for 6 years up until the spring of 1811. However, there are good grounds for supposing that he was probably there in about 1807/8-1812. By 1815 the school's name had changed to Eden House but it is unlikely that the premises changed. The last known advert for Aislabie's school is from July 1815 but there is no strong reason to suppose that he did not stay in business for a few years beyond then. He died on 11 November 1818 at the age of 44. That same month his premises were sold to the Guardians of the Poor of Kirkby Stephen and turned into a workhouse.

Aislabie advertised in the Liverpool press and seems to have concentrated on the north-west as his catchment area - Liverpool in particular but also Warrington and Manchester. He had agents in all three places and visited Liverpool and Manchester periodically. In 1815 he claimed that almost one hundred families in or near Liverpool could provide references. (We also know of pupils from Edinburgh, Coleraine, St Lucia and Kirkby Stephen.) Aislabie styled his school The Classical and Commercial Academy. This characterisation would clearly have appealed to a wide range of parents, promising both the traditional education of a gentleman and the more practical skills of a merchant. In 1808 Aislabie charged 15-21 guineas per annum, depending on age; in 1809, 16-22 guineas; in 1811, 18-23 guineas. In 1812 he put the prices up again and charged in pounds (£20 under 11 years old; £22 above 11 and under 14; £25 above 14 and under 18). These prices represented a lot of money for the time but were half what was charged at many other institutions further south. Profit had to be found in paring living expenses for the pupils.

In his adverts Aislabie proclaimed that as long experience has convinced Mr. A. that the usual vacations tend to impede the progress of education, his pupils do not visit home but at the particular request of their parents. Many other schools took this line: the educational case may have had some slight merit, and no vacations meant far fewer problems of transportation for all concerned. However, it is hard not to espouse the common perception that most parents were perfectly content for their offspring to be out of the way for years on end. As noted earlier, in the case of the young Walmsley, there were good reasons why his father would have wished him to be sent away from home.

Walmsley was complimentary about the health of the pupils (with just one death in his six years there) but this may be too rosy a picture given that the Kirkby Stephen parish registers record the deaths between 1807 and 1815 of seven schoolboys (not to mention Aislabie's own 10-year old daughter) stated to be either at the Academy or from distant locations. Even so, for the time, just one death a year would have been considered a better outcome than could be expected.

> Children of Sir Joshua Walmsley