This quest to identify Mr. Aislabie's Academy at Eden Hall grew out of earlier work on the Walmsley family from Liverpool and, in particular, it's most famous member, Sir Joshua Walmsley (1794-1871). Sir Joshua spent six years at Eden Hall and the biography of him by his son Hugh includes some colourful reminiscences. These have now been added to the Walmsley pages but, for the benefit of those more interested in the history of Westmorland or 19th century education, here is the sum total of what we have discovered. Whatever the quality of the school, for 10 years or more it occupied a prominent place in the life of Kirkby Stephen and so it's strange that so few traces survive.

The evidence is set out in three parts under the headings Richard Aislabie, Location of Eden Hall and Education at Eden Hall. We've tried to get back to original sources but this isn't possible in all cases. Hopefully some of the information presented will spark off further recollections and ideas.

Richard Aislabie was born in Bowes in 1774, the third son of Michael Aislabie, a butcher, and Martha Binks. Their fourth son Thomas, born in 1779, also features in this story. The family's Westmorland connection began with Richard's uncle John, another butcher, who married Margaret Salkeld from Brough in 1771. The couple's children were baptised in Bowes but at some point they acquired land - presumably through inheritance - and settled as farmers around Church Brough. At the time of the 1829 Parson & White trade directory, Thomas was a yeoman farmer, William's son James a farmer and Michael another farmer (and probably the person of that name with a butcher's shop in Market Brough). Richard Aislabie may, as Sir Joshua Walmsley claimed, have owned a large farm but it seems more likely that he was a tenant. He was, however, able to go grouse-shooting over the moorland between Kirkby Stephen and Bowes and so either owned a tract of Stainmore or was allowed onto the land of his relatives. There is no evidence that he subsequently owned any of the premises used for his school in Kirkby Stephen.

Nothing is known of Aislabie's academic background. He does not feature in lists of Oxford or Cambridge alumni but could have attended another seat of learning. However, unlike John Adamthwaite at Winton House and other contemporary schoolmasters, he never mentioned any qualifications in his adverts. The lack of obvious qualifications for teaching was no obstacle in this period to running a private academy! For a period he was joined by his younger brother Thomas, who certainly seems to have lacked any academic background. When he ceased his connection with the school, Thomas became a grocer. However, another brother, William, also became a schoolmaster.

In about 1798 Aislabie married Elizabeth Malkin from Clowne, near Chesterfield, in Derbyshire. Between 1799 and October 1807 they baptised no less than seven children in Clowne. Three more children were baptised in Kirkby Stephen between 1811 and 1815. Aislabie probably moved to Kirkby Stephen and began teaching there in late 1807. Parkinson's Guide and History of Kirkby Stephen (c1920) states that in 1807 Mr R. Aislabie was headmaster of the Eden Hall Seminary of Education for Boys. The 1807 date looks right but, as we shall see, Eden Hall was not the original name. A schoolboy from Liverpool died in Kirkby Stephen in December 1807; he was probably at Aislabie's school. For his part, Walmsley recalled that he had attended the school for 6 years up until the spring of 1811. However, from other evidence, it seems unlikely that he was there as early as 1805/1806 and left before 1812.

In February 1808 this splendid advert in the Manchester press (the earliest known for Aislabie's school) proclaimed the desirability of education by Messrs Robinson and Aislabie at Vicarage House in Kirkby Stephen. Aislabie would appear to be the junior partner in the business and the mention of numerous families being able to provide references strongly suggests that the school was in existence for some time (possibly several years) before Aislabie's arrival. Vicarage House, described in the advert as an elegant, extensive, modern building, very pleasantly situated in a salubrious air, and peculiarly calculated for the purpose of an Academy, was built overlooking the River Eden in about 1760 by the then vicar, Henry Chaytor. The 1829 trade directory, echoing the advert, described it as a neat mansion, pleasantly situated above the Eden. The building was demolished in the last century to make way for a new vicarage. Sporadic adverts in Liverpool, Manchester and Lancaster newspapers indicate where Vicarage House Academy sought to find its pupils.

In January 1809 The Times recorded that the partnership between R. Aislabie and T. Robinson, schoolmasters of Kirkby Stephen, had been dissolved. The identity of Robinson is unclear, although it is interesting that the Rev. John Robinson, DD, the minister of Ravenstonedale also ran a school called Ravenstonedale Academy. Conceivably, T. Robinson was a relative. In any event, Robinson and Aislabie parted company at the end of 1808. At the beginning of 1809 the two schoolmasters, now rivals, managed to place adjacent adverts in a Manchester newspaper. Aislabie was left as sole proprietor of Vicarage House, while his former partner was running Mr Robinson's Academy at Ormside, near Appleby.

The baptisms of Aislabie's last three children in 1811, 1813 and 1815 do not provide any additional information on his occupation or abode. He is simply recorded as a schoolmaster. The mortality rate of Aislabie's children was surprisingly high. Five of the seven children born in Clowne died as infants or very young. A sixth died of the fever in Kirkby Stephen in 1815 aged 10. Of the three children born in Kirkby Stephen, Elizabeth survived and subsequently married; Thomas died in 1816 aged 3 and Richard (the second child to be named after his father) died within weeks of his birth in 1815. The only children who lived long enough to marry were Elizabeth and her older sister Jane.

In 1810 and 1813 Aislabie, whose position as a schoolmaster demanded total respectability, had two most unwelcome run-ins with the authorities. In August 1810, just one day after the Glorious Twelfth, he was caught hunting game by John Sayer, one of the proprietors of Gilmonby Moor to the west of Bowes, and received a summons to appear before a Justice of the Peace. Sayer's complaint read:

This (abbreviated) description of who could hunt game is fascinating in its own right. The punishment of poachers in this period was still severe and offenders from the wrong social classes were liable to transportation. We do not know Aislabie's side of the story nor the outcome of the case. However, the complainant evidently believed that Aislabie was neither the owner nor lessee of any substantial property. Aislabie may still have owned or leased a small farm or other estate but it appears that he was not quite the landowner portrayed by Joshua Walmsley.

Then, in 1813, Aislabie had to settle with the Guardians of the Poor of Clowne. One Elizabeth Mellers, late of Kirkby Stephen, had become pregnant and was now in Clowne. Aislabie and John Malkin of Clowne (probably a close relative of Aislabie's wife) issued a bond agreeing to indemnify the parish of Clowne against the costs of the pregnancy and birth of a child. It is not stated who the father was but one may infer that the matter involved a member of the Aislabie-Malkin clan.

In the period 1811-1815 there are various adverts in the Liverpool press for Aislabie's school, now described as being at Eden Hall or (later on) Eden House. The Liverpool-Manchester area was still the main source of pupils and Aislabie regularly made visits there to meet prospective clients. In early 1815 (but not later that year) Aislabie shared the billing in his advert with his brother Thomas. Thomas may have been associated with the school a few years earlier since the young Walmsley attributed his departure from the school in 1811 (though probably a bit later than that) to a run-in with Aislabie's brother. When Thomas married in Kirkby Stephen in 1814 he gave his occupation as schoolmaster.

The last known advert for Aislabie's school is from July 1815 but there is no strong reason to suppose that he did not stay in business for a few years beyond then. He died on 11 November 1818 at the age of 44 but it is not known where he died or was buried. (Since he was not interred in Kirkby Stephen or Bowes, it is most likely that he was buried in or near Liverpool.) He died intestate and - for a man of his position - this suggests that he died suddenly. Aislabie had a few small effects in Liverpool (worth less than £20) and, because there was no will, it was not until 1822 that his widow Elizabeth succeeded in getting the Diocese of Chester to grant her administration. Aislabie almost certainly had other effects (and possibly a small estate) in Kirkby Stephen but there is no equivalent administration in the Diocese of Carlisle. One possibility is that he also had possessions (and land) out towards Bowes in Yorkshire and that administration would have been determined elsewhere but nothing has been found in the Province of York.

After her husband's death Elizabeth stayed in Kirkby Stephen until at least 1822. What became of her thereafter is as yet unknown. Her daughter Elizabeth married Thomas Race, a miller, in Kirkby Stephen in 1835. They had several children and Thomas plied his trade locally at Stenkrith Mill. The other surviving daughter Jane married John Loadman, a miner, in Kirkby Stephen in 1841.

Thomas Aislabie stayed in Kirkby Stephen for a few years after his brother's death. He had married Elizabeth Rudd, originally from Brough, in 1814 and they had four children in Kirkby Stephen between 1814 and 1820. However, by 1829 they had moved to Kingston-upon-Hull and Thomas was working as a grocer. The two eldest sons became a cabinet-maker and an upholsterer. At some point Richard's younger brother William found employment, as Richard had done, in Derbyshire. He was an assistant master at Repton School from 1818 to 1827 and then headmaster in Church Broughton from 1835 till his death in 1844. Could he have been one of Richard's assistants in Kirkby Stephen up until 1818?

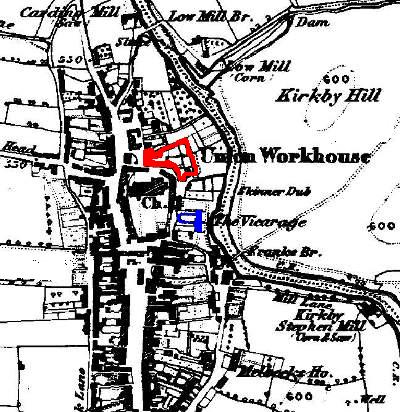

There is no original document which states definitively that Eden Hall/House was on the site of the later workhouse in Kirkby Stephen. However, a combination of process of elimination, the collective memory of local historians and other circumstantial evidence relating to property transactions strongly suggests that the siting is correct. The site in question is on The Green to the north of the parish church. Some nearby buildings of the period survive but the workhouse (later Eden House) was demolished a few decades ago to make way for modern housing. Amazingly, no photographs of this part of the workhouse have been tracked down. The only depictions known to us are drawings by Anne Anderson in her (and Alec Swailes') book Kirkby Stephen (1985): see pages 67-68 and also 59-60 and 65-66. A photograph is much needed (not least for Peter Higginbotham's admirable workhouses web site). Even Thomas Fawcett, who sketched most of the centre of Kirkby Stephen as he remembered it in 1817 when he was a small child, ignored this prime location.

From the drawings by Anne Anderson, the main workhouse building was a large three-storey stone edifice with a small classical portico. It was adjacent to a row of small houses. Most of the facade was in the form of a large country house but the end next to the churchyard had much smaller windows and presumably served a different purpose. From maps it seems that two large wings extended behind the building. It is this main workhouse building that constitutes the best candidate for the grandly named Eden Hall.

From Sir Joshua Walmsley's account, Eden Hall was very definitely in or very close to Kirkby Stephen. The only other substantial private school of this period in close proximity to Kirkby Stephen was the academy at Winton House run by the Rev. John Adamthwaite. However, both schools were advertising their services in 1815 and so were clearly separate institutions. Braithwaite's guide-book Kirkby Stephen (4th ed. 1922) states that there was previously a private school on the site of the workhouse and that it was run by Mr (Henry Abel) Arrowsmith before he succeeded Adamthwaite at Winton. The latter assertion seems mistaken because the workhouse had already taken over the site before Arrowsmith commenced his teaching career. Arrowsmith is firmly connected to Brough: his children were baptised there and, before he took over at Winton, he ran Mr Arrowsmith's Academy in Brough. As mentioned above, Parkinson's Guide, also from the 1920s, agrees that the workhouse building was previously, amongst other uses, a private school run by Aislabie.

Archive documents in the Cumbria Record Office relating to the workhouse shed light on previous use of the buildings. In 1803 George Dickinson, a manufacturer, acquired a (mid-18th century?) house plus outbuildings, garden and orchard adjacent to the north side of the churchyard for £292. By 1807 Dickinson was simply the tenant and the owners apparently Peter de Graves and Deborah Decharme of London. Parkinson's Guide talks of a company called Graves, Lane & Co, which erected the building that was to become the workhouse as a cotton mill and soon after became bankrupt. When the premises changed hands again in 1807, their value had increased to £1,500, reflecting the addition of sizeable new buildings, although these were not specified. The new owner in 1807 was John Dand, a Carlisle manufacturer, who also thought he could flourish as a banker. Unfortunately, he too became bankrupt in the spring of 1808. When sold to the next owner, Richard Binks, a merchant from Kingston-upon-Hull, for £1,440 in early 1809 the premises were described as customary messuage and tenement lately rebuilt and new-modelled and now called The Manufactory in town and manor of Kirkby Stephen ... with all houses, shops, warehouses etc.; and machinery looms etc.; also machinery frames for dressing cotton warps. etc. in Stenkrith Mill. This is the first clear indication that the prime purpose of the buildings was cotton manufacturing and there is no mention of any schoolrooms.

Binks remained the owner until November 1818, when he sold all the premises for £1,500 to the Guardians of the Poor of Kirkby Stephen. (This is the beginning of the workhouse. In 1840, after the Poor Law Act of 1834, ownership was transferred for a consideration of £850 to the East Ward Union. Then in the 1930s the workhouse received a slight facelift and became Eden House. It was demolished in the 1970s. ) The description of what Binks sold is of high interest: messuage and tenement called The Manufactory consisting of dwelling house, schoolrooms, cowhouse, stables, coal-house, rooms called the banking house, bakehouse, pig-styes, shed and other buildings with yard and garden adjoining and all erections and buildings lately used as a manufactory ... all on north side of church-yard in Kirkby Stephen. Here we have the crucial first mention of schoolrooms. Given cramped teaching and sleeping conditions, a school would not have taken up a vast amount of accommodation and need not have been the only business carried out on the Manufactory premises.

In all this archive data there is no mention either of Richard Aislabie (or any other schoolmaster) or of Eden Hall/House. The name Eden Hall was seemingly an eye-catching invention of Aislabie to attract clients. Whether the Eden House of the 20th century owes anything to Aislabie is unclear. It might be a throwback to earlier times or just an obvious name for a property close to the River Eden. Anyway, unlike some of his contemporaries, Richard Aislabie evidently did not own his school premises. However, Richard Binks was none other than the younger brother of Aislabie's mother Martha; he was also her executor. His purchase of the Manufactory was clearly done on Richard Aislabie's behalf and thus may have drawn on Binks money held in trust for Martha and her offspring. (The Binks family connection also explains why Thomas Aislabie left Kirkby Stephen and set up in Kingston-upon-Hull as a grocer.)

The dates of property transactions tie in neatly with known events in Aislabie's life. His teaching career in Kirkby Stephen appears to have begun in 1807 but initially the school was in Vicarage House and remained there into 1809. The bankruptcy of Dand in 1808 meant that the Manufactory would almost certainly change hands again. In January 1809 Aislabie's partnership with Robinson was dissolved and then Binks acquired the property in April. Aislabie was now free to run his own educational enterprise. It seems likely that Aislabie transferred his school from Vicarage House to the Manufactory/Eden Hall in mid-1809. He died on 11 November 1818. The conveyance of the property to Kirkby Stephen's Guardians of the Poor commenced on 13-14 November. Did Aislabie's death perhaps facilitate a planned deal? Or did the prospect of a sale over his head and the loss of his livelihood bring about his sudden death?

Aside from Sir Joshua Walmsley's picaresque description of life at Eden Hall in about 1807-1812, any attempt to portray the school has to depend on a series of newspaper adverts and comparisons with other schools of the time. To judge by the flood of adverts in The Times and other newspapers in the first decades of the 19th century, the school business was booming and was as cut-throat as other forms of commerce. The north of England was apparently the favourite location for private schools, perhaps because it was cheap and out-of-the-way. In this period virtually every town in the vicinity of Kirkby Stephen had at least one academy and often two. The list includes Winton, Ravenstonedale, Brough, Ormside, Cotherstone, Bowes and Barnard Castle. The schools advertised similar educations and charged much the same price. One fears conditions were also broadly similar and that what Dickens described in Nicholas Nickleby was not untypical (nor considered unacceptable by many parents). There was evidence of poor treatment well before Dickens and the schools still flourished.

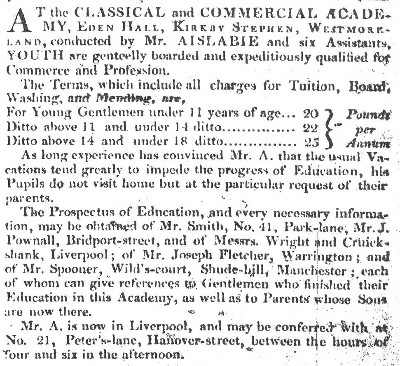

Aislabie's characterisation of his school as The Classical and Commercial Academy would clearly have appealed to a wide customer base, promising both the traditional education of a gentleman and the more practical skills of a merchant. By 1815 the location had changed to Eden House but it is unlikely that the premises changed. Walmsley recalled that Eden Hall had 130 boys. His father had sent him there because he could no longer afford the fees of what sounded like a pleasant academy just outside Liverpool but which charged more than half as much again. In 1808 Aislabie charged 15-21 guineas per annum, depending on age; in 1809, 16-22 guineas; in 1811, 18-23 guineas. In 1812 he put the prices up again and charged in pounds (£20 under 11 years old; £22 above 11 and under 14; £25 above 14 and under 18). These prices represented a lot of money for the time but were half what was charged at many other institutions further south. Profit had to be found in paring living expenses for the pupils. Walmsley describes very meagre fare. In a celebrated court case of 1823 about conditions at Bowes Academy the pupils bemoaned the paucity of meat and the absence of any supper and described a dormitory of 30 beds with up to 5 boys in each. The defence claimed that meat was served three or four times a week and that never more than three boys shared a bed! Eden Hall cannot have been significantly different: at least, it served meat three times a week.

In his adverts Aislabie consistently proclaimed that as long experience has convinced Mr. A. that the usual vacations tend to impede the progress of education, his pupils do not visit home but at the particular request of their parents. Many other schools took this line: the educational case may have had some slight merit, and no vacations meant far fewer problems of transportation for all concerned. However, it is hard not to espouse the common perception that most parents were perfectly content for their offspring to be out of the way for years on end. According to Walmsley, for some hours each day the pupils worked on a large farm owned by Aislabie. The 1818 description of Binks' property mentions a cowhouse, stables and pig-sties. Whether this was Aislabie's farm is unclear: it sounds a bit modest and perhaps he had his own estate further afield. All things considered, Walmsley was not without praise for his school. In particular, he reckoned it a healthy place with just one pupil having died during his six years there. This may be too rosy a picture, The Kirkby Stephen parish registers record the deaths between 1807 and 1815 of seven schoolboys (not to mention Aislabie's own 10-year old daughter) stated to be either at the Academy or from distant locations. Even so, for the time, just one death a year would have been considered a better outcome than could be expected.

Aislabie did not advertise in The Times and seems to have concentrated on the north-west as his catchment area - Liverpool in particular but also Warrington and Manchester. He had agents in all three places. He visited Liverpool regularly and had some personal effects there. In 1815 he claimed that almost one hundred families in or near Liverpool could provide references in respect of pupils who had attended his academy during the last six months. Later that year, he modified the claim to over 300 families (but without any limit on the timeframe). If such figures from advertising are reliable, then the vast majority of Aislabie's pupils came from the Liverpool area. Of the seven schoolboys who died at the academy, two were from Liverpool, one from Edinburgh, one from Coleraine, one from St Lucia, one possibly from Kirkby Stephen and one from an unrecorded location.

Aislabie was helped in his work by 5 or 6 Assistants and for a period by his brother Thomas. Such assistants could be experienced schoolmasters without the means to run their own school or senior pupils. Walmsley, who left Eden Hall at the age of about 17-18, spent some of his time as an assistant. Amongst other things he ran the school's accounts, preparing the bills for parents, and hunted grouse on the moors for sale in the market. Since his father had died by then, his post must have relieved him of any fees for continuing study and provided a modest income. However, having had his argument with Aislabie's brother (Thomas?), he left Eden Hall abruptly with only a few shillings left in his pocket after paying for his coach fare back to Liverpool.

This article has benefitted from the enthusiastic help and advice of the Cumbria Record Office in Kendal, the Durham Record Office and quite a few experts in Westmorland history. In particular, thanks are due to: Douglas Birkbeck, author of A History of Kirkby Stephen (2000), for information from Parkinson's Guide; Bob Adamthwaite for providing his article The Seven Reverends Adamthwaite; Sheila Wilkinson for uncovering and transcribing a wealth of information in parish registers relating to Aislabie and his pupils; and Alan Leng for generously providing material from his one-name study of the Aislabies.

> Joshua Walmsley's Schooldays

> William Shaw and Bowes Academy